It was November 2012, and the good people of Colorado were about to buck their leaders. A grand total of two Colorado legislators supported a constitutional amendment to legalize the recreational use of marijuana.

The people paid the detractors no mind. The vote wasn’t even close.

Soon, Washington voters passed a similar measure, with Alaska and Oregon poised to follow.

The usual suspects harrumphed and wailed, promising chaos, crime, and social decay.

Children’s brains would be arrested by fog—if they didn’t die first by fiery car crash.

Business groups warned that workers would lose all will to produce, then sue for being fired.

Eight states passed marijuana laws in 2016. Nevada, which kicked off recreational sales on July 1, has seen weed shortages ever since due to high demand. Associated Press/John Locher

Police argued that disrupting gangs’ dominion over the black market would fuel violence.

Lawmakers worried they would incur the terrible fury of the federal government, which still legally considered weed to be heroin’s equal.

Five years later, the apocalypse seems to have missed its appointment. Instead, farm towns are cultivating a new cash crop and merchants have driven life back into vacant factories. New retailers resemble modern vitamin shops, rather than the dingy head shops opponents imagined.

Meanwhile, a billion-dollar upstart industry has crippled the black market, put thousands to work, and fed hundreds of millions in new tax dollars to schools, police, roads, and health care.

These days, legal marijuana’s greatest danger is not crime or decay, but politicians’ bitter disputes over who shall eat first from this glorious new pie.

Minnesota has no pie. Not even a crumb. The state’s medical marijuana program was crippled in gestation by the police lobby, so restrictive that dispensaries registered a combined loss of $11 million in the first two years.

Now Minnesota faces a looming decision. A majority of states already have medical marijuana. The new frontier is legalizing recreational use. Four more states did it in November, and public acceptance is accelerating.

If our state politicians aren’t careful, they may soon find themselves run over the same way Colorado’s were. Luckily, the trailblazers have already forged paths of success and failure for us to learn from.

The Colorado gold rush

In the summer leading to Colorado’s constitutional amendment, state Rep. Jonathan Singer found himself trying to sell recreational weed to middle-class voters at the Northglenn Recreation Center in suburban Denver.

To many of Colorado’s progressives and libertarians, legalization was the obvious rejoinder to a failed war on drugs. For conservatives and family-oriented Democrats, Singer’s pitch needed to hit closer to home.

Northglenn’s beloved rec center had been around for some 20 years, the soul of the community, home to a senior center and a theater. But it was falling apart. Marijuana taxes could restore its full dignity, Singer told the crowd. Residents began to see the possibilities.

After the law passed, Northglenn would welcome five marijuana shops, which generated $730,000 in local taxes in a single year. In 2014, voters passed a hike in the suburb’s weed tax, directing proceeds directly to the rec center.

Colorado’s 15 percent tax on wholesale marijuana, 10 percent on retail, and 2.9 percent everyday sales tax puts it on course to raise more than $200 million this year. The first $40 million went to the Department of Education to replace crumbling roofs, repair bleachers, and treat asbestos in rural schools. Millions more have been spent on dropout and bullying prevention, police training, and prison diversion for juvenile offenders.

Counties and cities are allowed to establish their own taxes. Last year, Denver received $37 million. Though marijuana regulation cost $9.5 million, the remaining $27.5 million bolstered the city’s general fund and went to affordable housing.

Police argued that disrupting gangs’ dominion over the black market would fuel violence.

Lawmakers worried they would incur the terrible fury of the federal government, which still legally considered weed to be heroin’s equal.

Five years later, the apocalypse seems to have missed its appointment. Instead, farm towns are cultivating a new cash crop and merchants have driven life back into vacant factories. New retailers resemble modern vitamin shops, rather than the dingy head shops opponents imagined.

Meanwhile, a billion-dollar upstart industry has crippled the black market, put thousands to work, and fed hundreds of millions in new tax dollars to schools, police, roads, and health care.

These days, legal marijuana’s greatest danger is not crime or decay, but politicians’ bitter disputes over who shall eat first from this glorious new pie.

Minnesota has no pie. Not even a crumb. The state’s medical marijuana program was crippled in gestation by the police lobby, so restrictive that dispensaries registered a combined loss of $11 million in the first two years.

Now Minnesota faces a looming decision. A majority of states already have medical marijuana. The new frontier is legalizing recreational use. Four more states did it in November, and public acceptance is accelerating.

If our state politicians aren’t careful, they may soon find themselves run over the same way Colorado’s were. Luckily, the trailblazers have already forged paths of success and failure for us to learn from.

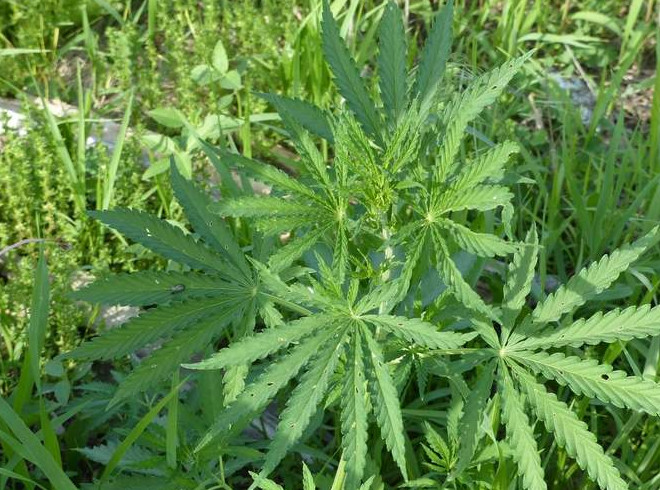

States with new recreational marijuana markets have created thousands of jobs from farming to budtending.

“Local communities across the state can look at places like Northglenn, or Pueblo, and say, ‘You know what? Things haven’t gotten worse there,’” says Rep. Singer. “In fact, they’ve gotten better and they’ve gotten better because of legalized, recreational marijuana.

“If you told me in 2011 that in just a couple of years I’d be passing statewide tax increases to help kids, and I’d be using legal marijuana dollars, I might ask what you were smoking.”

An off-the-charts windfall

Washington’s sunny valleylands are blessed with an arid climate and a long growing season, making it one of the best places in the famously rainy Pacific Northwest to cultivate huge tracts of marijuana.

Since sales launched six months after Colorado’s, legal weed has bled $1.5 billion from Washington’s black market. It’s the state’s fastest growing new revenue stream, with receipts totaling a stunning $260 million a year, thanks to a beefy 37 percent tax. Next year is expected to bring in more than $300 million.

In their 2012 ballot initiative, voters chose to earmark earnings to provide health care for the poorest of the poor, rehab for pregnant women addicted to opioids and meth, new beds in juvenile drug treatment centers, and mental health care for kids.

A dropout prevention program, whose budget was plundered during the Great Recession, received a boost from marijuana dollars, raising graduation rates in once-maligned districts by 30 percent.

“Typically that’s followed with a spike in use, when you see the perception of harm go down, but that hasn’t happened as of yet,” he says. “We have seen other drug use patterns come down—tobacco, alcohol, and such.”

But by targeting social services, rather than adopting Colorado’s flexibility, some are feeling left out of the state’s new bounty. It’s also created the perfect environment for politicians to do what they do best: squabble over the riches.

Things aren’t going as swimmingly in Spokane County, says Commissioner Al French.

Marijuana brought Spokane thousands of new jobs and returned vacant warehouses to life, but when the bud flowers for harvest, whole towns reek like a skunk invasion. Unlike Colorado, which generally requires weed to be farmed indoors, Washington permits outdoor grows. Dealing with odor complaints has cost Spokane $1 million, while property values have been reduced.

Marijuana taxes don’t cover the costs of regulation, French says. Not because weed isn’t generating revenue, but because the state is hoarding it.

In the legislature, the new revenue has sparked partisan tugs of war. Politicians have raided weed coffers to shore up Washington’s finances—and pay for their past mistakes.

In 2012, Washington’s Supreme Court found the government in contempt for underfunding education. Schools were perpetually short-staffed with overcrowded classrooms. Teachers were paying for basic supplies from their own pockets, while parents had to fundraise for art and music. Washington was fined $100,000 for every day it failed to remedy the situation.

Republicans wanted to circumvent voters’ wishes by pouring all the marijuana money into K-12 education. Democrats fought back.

These days, the eternally vigilant Sen. Reuven Carlyle (D-Seattle) plays guard dog to ensure dollars earmarked for health are actually spent on health.

“I think there has already become an unanticipated windfall at a magnitude that’s just off the charts, no question about that,” he says. “Now the question is, ‘How do you responsibly manage that rather than turning into a drunken sailor?’ You have to be smart.”

At the end of the day, tens of millions of pot money got funneled to education anyway. Republican Rep. Cary Condotta is happy about that.

The biggest flaw in Washington’s rollout, Condotta maintains, was the insult to local government. Only $6 million is spread across the state’s entire roster of marijuana-selling counties, not nearly enough to cover new costs of enforcement and regulation. He’s been trying to raise that to $10 million, without much luck.

Nevertheless, folks on both sides of the aisle agree that legalization has been an unequivocal success. The gravy’s thicker than expected, the problems far fewer. Critics grumble about increases in marijuana-impaired driving, but Condotta chalks that up to law enforcement taking a novel interest in searching for it when they never looked so hard before.

Every day, conversations around marijuana become less hysterical, and more mature.

The land of lumbering resistance

The leaders of legal weed states are proud to say they’re receiving many marijuana tourists these days. Diplomats from Germany and France, who have made pilgrimages to Denver, Seattle, and Portland, are convinced they must study now for inevitable legalization in their own countries.

Canada is on the brink. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau introduced legislation in April, fulfilling a campaign promise that helped him gain office.

But what matters most to the small, free-thinking states taking the first step is that others join their ranks. As more states embrace the idea, congressional power tips against any thought of federal interference.

They envision a day when the feds no longer deem weed a controlled substance. A day when insurers include it in health policies, when banks won’t fear a crackdown for servicing marijuana businesses.

California, with its heavy-hitting 55 electors, was a big recruit to the cause last year. Minnesota, meanwhile, has its transmission frozen in neutral.

There’s no doubt of strong public interest, but the state legislature is increasingly prone to dysfunction, rather than bold moves.

Three years ago, it was with lumbering resistance that Minnesota passed one of the most restrictive medical cannabis programs in the nation. So few conditions qualified—amputees couldn’t get it for phantom limb pain, and cancer patients had to either suffer great pain or have less than a year to live—that the market generated few customers.

Prices remained prohibitively high, so those who managed to get a medical license still had to rely on the black market.

Doctors are just as fearful as politicians. Physicians who work for major hospitals, wary of becoming typecast as pot doctors, won’t publicly say if they certify patients. Only two independent clinics advertise the service.

Dr. Jacob Mirman of Life Medical in St. Louis Park is mystified by his colleagues’ reluctance to embrace a medication proven to treat pain without the risk of addictive opioids. From the Hippocratic, humanitarian perspective, “You can’t not do it,” he says.

“People are reporting a lot less pain, a lot less spasms. They’re sleeping better, they’re getting off their narcotics. There’s really no negative here, except the cost.”

It’s frustrating, Mirman says, that while people across the state are journeying to his clinic for marijuana certification, the vast majority of his regulars—the elderly, disabled, and low-income—can’t afford the opportunity to break their opioid dependence.

Struggles in bungling Oregon

There are headaches that come with constructing a good regulatory framework from scratch. Yet so far, the problems stem not from the dangers of weed, but the chronic affliction of poor government.

Legalization came to Oregon two years after Colorado and Washington, producing some of the finest bud ever cultivated on God’s green earth. But the byproducts of a bungling government were almost immediate.

Costly lab testing regulations, which certify organic bud only, have created a backlog of legal weed. That’s left dispensaries occasionally short of wares, while weed is stockpiled in storerooms—and occasionally leaked into the more efficient black market.

Nor is Oregon generating the tax windfall seen in other states. It reaped just $79 million since the start of sales last year. Much of this is a product of Oregon’s longstanding aversion to sales tax, which prevents the government from imposing anything more than 17 percent at the point of sale, plus a 3 percent local tax.

That’s still $79 million Oregon didn’t have before. But when the state’s running a $1.6 billion budget gap, “that doesn’t amount to a hill of beans,” says Rob Bovett, attorney for Association of Oregon Counties.

For many Oregonians, legalization has been an ordeal in managing expectations. Revenues haven’t manifested in tangible improvements to ordinary people’s lives.

“A lot of folks still believe that marijuana legalization was going to be the end-all, be-all, save-all for local government, the economic distress that we have in our school systems,” Bovett says. “Throwing an additional $30 million into our education system, I don’t want to call it chump change, but it really isn’t going to save anything.”

Add in Oregon’s black market leakage—the consequence of producing too much desirable weed for Oregonians alone to smoke, try as they might—and the jury’s hung on whether marijuana will eventually prove to be worth the aggravation.

Eventually, 40 percent of the revenue will go to schools, to be spread thin via a complex formula directing funds to the districts that need it the most. Twenty-five percent will go to health; 15 percent will pay for major crimes investigations by the Oregon State Police; and 10 percent is reserved for city and county law enforcement.

Sen. Ginny Burdick is upbeat about the possibilities.

“It’s not a huge amount of money, but it’s better than nothing,” she says. “The initial signs are good.”

There is also the expectation that with time, the state’s growing pains will fade. The backlog for lab screening has nearly expired, says Bovett.

He anticipates that someday, Oregon’s weed will not only be price-competitive, but of such quality that neither the black market nor other states’ legal markets can compete. And should Oregon consider raising taxes, it could be a break for local governments.

A tide in the affairs of men

In February, four DFLers stood shoulder to shoulder in a dusty Senate Building room in St. Paul to announce a gaggle of bills aimed at legalization. One was a traditional piece of legislation to be decided by lawmakers. Another proposed amending the state constitution to make cannabis use a right, such as hunting and fishing.

It was a crapshoot strategy guaranteed no hearings in a Republican-controlled legislature, and no support even from the Democratic governor.

Adversarial reporters wanted to know whether these legislators were private stoners. Reps. Tina Liebling of Rochester, Jason Metsa of Virginia, Alice Hausman of St. Paul, and Jon Applebaum of Minnetonka each timorously responded that they were not, though all but Hausman owned up to giving it a try.

The point of the cheeky exercise seemed to be just saying something, anything publicly about recreational legalization, to chip the glacial taboos of dubious voters. They noted the social problems caused by prohibition—nearly 7,000 arrests in 2015, carried out on African Americans at a rate of nearly 10 times higher than whites, though blacks statistically use only slightly more than whites. A new made-in-Minnesota industry would funnel money to schools and deliver property tax relief to the people, they argued.

“Let’s be real. This isn’t about, ‘Are people going to use it?’” Leibling said. “They are using it. The problem is they’re buying it on the black market. They don’t know what’s in it. It’s putting them in contact with the criminal element because that’s how you buy it.”

None of the bills budged. Instead, Republicans moved backward, suggesting a freeze in the medical conditions allowed in the existing program, and championing the reopening of a private prison in Appleton.

It was exactly as weed advocate Oliver Steinberg of MN NORML predicted. “Anything we accomplish in 2017 will simply have to be a step in a long process. But maybe we could take that step.”

Steinberg, a scrappy septuagenarian, carries a wealth of marijuana history in his head and a flip phone in his pocket. He leads the local chapter of NORML with Michael Ford, a thirtysomething cancer survivor with a celebrity-sized social media footprint on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

They’re volunteers, hoping to put an organization funded entirely by dues-paying, everyday people in the same ring as lobbyists bankrolled by Big Pharma. In a legislature where money carries the day, theirs is a David vs. Goliath fight. So they’ve set their sights on a constitutional amendment, which would allow the voters to bypass their leaders.

“If we can give people the vote, I think it’s going to get a ridiculous amount of votes,” Ford says.

Steinberg likes to quote Julius Caesar to describe marijuana’s popular support. “There is a tide in the affairs of men. Which, taken at the flood, leads on to fortune.”

He sees it in the way beat cops stuffed dollar bills in NORML’s jar at the Open Streets festival last year. He sees it in the 31,000 votes for the Legal Marijuana Now candidate in the 5th Congressional District, a guy nobody remembers because he had no campaign, no organization, no money, and no name recognition.

In 2014, a similarly broke candidate got 57,000 votes for attorney general, and he wasn’t even a lawyer.

People cast their ballots for the Legal Marijuana Now party name, which was both a political platform and a rallying cry.

There’s a persistent myth that states like Colorado are different, that their western sense of freedom allowed liberals and libertarians to join hands in a way that could never happen in Minnesota, where the left is cautious and the right still holds Reefer Madnesssensibilities. But according to Mason Tvert of the Marijuana Policy Project, Colorado’s road to legalization was just as long, cutthroat, and seemingly impossible as Minnesota’s path appears today.

In 2005, Tvert moved to Colorado with the explicit goal of building public support for a first-of-its-kind initiative. He started an organization with the single-minded purpose of educating the public, working tirelessly over seven years to increase the percentage of people who recognize that marijuana is safer than alcohol.

Establishing a medical marijuana system is the first step.

“It allows people to see that there’s a way to do this,” Tvert says. “That the federal government would allow it. That you could have businesses openly operating, following the rules, localities that choose to ban them and others that choose to accept them. That it wouldn’t cause problems. And people could see them and see they were professionally run businesses.”

credit:420intel.com